Trinity College, Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MS R.4.23.

(Copyright of the Master and Fellows, Trinity College, Cambridge).

Commentary provided by Professor Catherine Leglu (University of Reading)

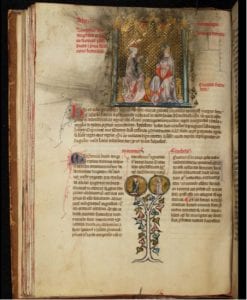

Trinity College Library, MS R.4.23, f. 53r

This image of Charlemagne clearly depicts him as the king of France. He is not wearing the imperial emblem or regalia (on this issue, see the forthcoming article by Adrian Ailes in the Further Reading section of this website). It is one of many copies of an illustrated genealogy of the kings of France compiled by the Friar Preacher (Dominican) Bernard Gui (c.1261–1331). It is one of two digitized copies of Bernard Gui’s genealogy in Cambridge college libraries. The other is in the Parker Library (Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 45), copied around the year 1331.

Bernard Gui is remembered nowadays as an inquisitor, but in his lifetime he was a prolific and influential compiler of archival and chronicle materials, producing lists and summaries that he called cathalogus (‘catalogue’). One of these catalogues is an account of the kings of France from the foundation of their lineage by Trojan exiles to the current ruler. He assists the reader by including an illustrated ‘tree’. This is regarded as one of the first examples of a ‘family tree’ diagram.

Gui is known to have supervised and corrected copies of his books. He seems to have worked closely with one scriptorium, and this was in all probability either the Dominican convent in Toulouse, where he lived and worked for sixteen years as inquisitor (1307–23), or commercial book artisans associated with the university of Toulouse. After he left Toulouse and took up residence as bishop of Lodève (1324–31), Gui’s production of books slowed down considerably until the last years of his life, when he published new and expanded compilations.

The content is typical of Gui’s working method. Several catalogues are put together in no particular order: a chronicle of popes, a chronicle of emperors, three lists of kings of France (one of these is the illustrated ‘tree’), a history of the major councils and synods of the Church, a list of the priors of the orders of Grandmont and of Artige, a list of seventy saints, and finally an expanded chronicle that is entitled the Flores Chronicorum. In this manuscript, all the documents except for the Flores Chronicorum were copied in the interregnum period between the death of Pope Clement V on 20 April 1314 and the death of King Louis X of France on 5 June 1316 (his accession to the throne in 1314 is described). Some additional notes bring the chronicle up to date with the election of his successor, John XXII, on 5 September 1316. The Flores Chronicorum was copied after May 1320 (f.164v). The codex was given consecutive page numbers, and a later hand worked on its coherence by adding notes on a few folios that provide the reigns of kings and popes up to Clement VII (1378–94). This was the first of the ‘antipopes’ of the Great Western Schism, and his successor Benedict XIII is also added (1394–1423). There are no owner marks and no dedication to a specific patron.

The Arbor genealogiae regum francorum is derived from older schemes. It was probably incorporated into Gui’s compilations around 1314, as it appears in every copy of the catalogue of the kings of France that was produced under Gui’s oversight after that date. The design of these ‘trees’ and their extended families did not change. The kings ‘of the Franks’ are an unbroken line of fathers and sons, dating from the foundation by exiled Trojans who had founded the city of Sicambria, then moved into Frankland. Gui presents three dynasties. The first runs from the Trojan exiles to the Merovingians. The second is the Carolingian dynasty, and the ‘third genealogy’ is the Capetian line, from their founder Hugh Capet to the current ruler. The text opens by telling the reader that the Arbor’s line of kings of the Franks includes the kings of Burgundy, Italy and England (f.49v). The Arbor’s content and therefore its messages about the legitimacy and continuity of the kings of France were fixed. However, there was considerable freedom for artists in how they depicted the heads and full-length images.

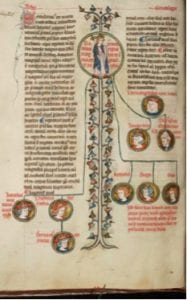

Trinity College Library, MS R.4.23, f.49v.

The founding fathers are exiled Trojans and they rule in harmony as co-rulers. They are Thucytus/Lurchytus (normally spelt Turcus) and Francion, son of Aeneas. Beneath them a tiny Marcomirus and Genebaldus, rulers of Sicambria, open the first tree. In between, the prologue explains the Arbor’s scheme. A circle designates someone special for their nobility or holiness. A crown designates a king or a queen. These men have no crowns, so they are not kings.

On the facing page, however, is the first sole ruler, Pharamond (f.50r). He is draped in a cloak depicting the royal French emblem, the fleur de lys, on blue ground. Thereafter, each king is shown in the trunk of the tree, and each king is represented in the clothing of a king of France.

On f.53 Pipin is shown standing on a lion, Berte’s head is next to him, in a circle. The rubric reads: ‘Here opens the second genealogy of kings of France’. The illustration of this folio would have evoked the legendary stories of Charlemagne’s lion-killing father Pipin and his heroic mother, Berthe ‘of the big foot’. Adenet le Roi’s prose romance Berte au grand pied, dates from the later thirteenth century.

Trinity College Library, MS R.4.23, f. 53v

Charlemagne is depicted in an unchanging family group in the copies of the Arbor. He is set in the centre of the tree trunk, depicted full-body. In the left margin are two crowned heads: Charlemagne’s descendants Pipin and Bernard, king of Italy. In the right, in a circle, there is a picture of his crowned wife, named as ‘Ermangarde’ (Hildegard). Below her on the right are Charlemagne’s sons by an unnamed concubine, Hugh and Drogo, bishop of Metz. Beneath them are the names of Charlemagne’s daughters, Rotrudis, Bertha and Gisela. Beneath their names are their three heads, without crowns.

For example, here is a copy made around December 1314, probably corrected by Gui himself (it is available through Gallica). Charlemagne is clad in blue, without a cloak, and he carries the orb and sceptre of the Holy Roman Emperor. There is no fleur-de-lys:

Paris BNF NAL 1171, f. 139v

In the same section of text (this time unusually combining the section devoted to Pipin, above Charlemagne) in a copy produced in Toulouse around 1317, Bibliothèque municipale de Toulouse, Ms 450, f.187r (c.1317), Pipin is not associated with a lion and neither king wears the insignia of the King of France. Interestingly, all the other kings from Pharamond onwards wear a sceptre with the fleur-de-lys. The Carolingians from Pipin to Louis the Pious, however, are depicted as emperors. Charlemagne does wear a blue cloak trimmed with ermine, but it is plain and he carries the orb and sceptre. The same design appears in a later copy, probably from the years 1320-40: Paris BNF NAL 779, f. 172 v (1320-40). Once again, the emperor is dressed in royal blue, but there is no fleur-de-lys. An additional three daughters have been added in the right margin, but otherwise the design is the same.

Gui absorbs Charlemagne into a lineage of reges francorum, but in some copies, the Carolingians are shown to be emperors, not kings of Franks. The Trinity Library manuscript’s Arbor is different, because it makes Charlemagne a French king. It is different also because it clearly cost more to produce than these copies. It gives the impression of a book that does not quite reflect Gui’s ‘house style’. Charlemagne is depicted as a young king of France, bearing the fleur-de-lys emblem on his sceptre and wearing the French king’s cloak of fleur-de-lys on a blue ground. The same image appears throughout the Arbor, so it is used for the last king in line, Louis X, who had just come to the throne at the age of 24.

The image of Charlemagne in Trinity College Library, MS R.4.23. within his family group (f. 53r) raises an interesting question about how these images were created.

Trinity College Library, MS R.4.23, f. 53r

The design is unaltered but Charlemagne’s daughters, Rotrudis, Bertha and Gisela have been depicted by mistake as three young men. Mistaking the gender of the three daughters is a serious and unusual error. The daughters’ names are in red ink. The rubricator was a scribe who wrote captions in red ink, and this manuscript has a few folios where instructions to the rubricator have been jotted in a lower margin, for example, on fol. 42v (this is in a section of the catalogue of kings of France discussing the reign of Charlemagne).

It would be typical for rubrics to be written in after the main text was copied in black ink. An artist would likely have worked from both written and spoken instructions, and in this case, the fact that the scheme of the genealogy is fixed implies that they worked from a visual model. As was noted above, the compilation is not produced in Gui’s ‘house style’ and this mistake implies that the Arbor was created by a team that was not familiar with other copies of the genealogy.

Artists travelled between centres of book production in this period. It is therefore likely that these images were produced by artists who came from a number of regions, working for a while in places such as Toulouse and Avignon. The images of the kings follow a strict basic design, but the artists were clearly free to vary the physiognomy and clothing of the kings and their families. This particular copy is a luxury product, with an artist of higher quality than usual employed to illustrate the Arbor. It employs expensive gilding and puzzle initials. Above all it is unusual in its use of the French royal heraldic design of fleur-de-lys and azure for the kings. An updated presentation copy of the Arbor was produced for King Philip VI in 1331 and it contains less expensive illuminations (Madrid, Biblioteca nacional de España, ms. 10126, f.152r). Here, Charlemagne is not wearing the emblems of the French crown. He is holding a sword and he is wearing red.

It seems clear that whoever commissioned this luxury copy in 1314–16 wanted it to serve the prestige of the reigning king of France, Louis X. Charlemagne is depicted as an ancestor and model for that young king. Sadly, Louis X was destined to die within a few months of the copy’s completion.